Rachel Wang, English Language Fellow, Indonesia, 2018-2020

When Rachel Wang arrived in her host city, Manado, Indonesia, as a Fellow (2018-2020), she soon realized that as an Asian American she blended into the city’s street life, often mistaken for a Chinese tourist or a local resident. It made sense: Manado, with its miles of oceanfront beaches, is a popular destination for vacationers from China, and her casual attire fit in nicely in Manado, a Christian-majority city in a predominately Muslim country. “Not standing out on a daily basis is great,” she says. “But it was frustrating when people were looking for the American in the room and failed to recognize me.”

Wang wanted to broaden her Indonesian students’ and colleagues’ understanding of what it means to be American, for them to appreciate that, like Indonesia with its hundreds of ethnic groups, the United States was a country of great heterogeneity. Wang chose to convey that message on the first day of each of her teacher trainings, workshops, and classes before the frequently asked question “Why do you have an Asian face?” was raised. Just as Indonesia has many ethnicities, she would offer, so does the United States. “My mother is Taiwanese, my father is Chinese, my father’s mother is Japanese, and I – born and raised in Madison, Wisconsin – am American,” she explained. To illustrate how her family drew from its multicultural makeup, she described in a presentation at her host institution, Sam Ratulangi University in Manado, how her family typically observed Thanksgiving Day – they would spread the celebration out over two days, feasting on traditional Thanksgiving fare on one day and Chinese hot pot on the next.

Being a Fellow or Specialist abroad can be challenging enough, with adjustments taking place on many levels, from language and food to attitudes and values. But Fellows and Specialists who are black, indigenous, or persons of color (BIPOC) have additional issues with which to contend: their race and identity. “Initially it felt like a burden, but increasingly I saw it as an opportunity to explain the diversity of America,” says Wang. Indeed, many of those she taught were unaware that America’s indigenous people were persons of color. “I explained to them that the difference between Indonesia and America is that in Indonesia the colonizers eventually left, but in the United States, they stayed,” she recalls. The America that grew from that history provided an opportunity to expand the idea of culture and country to include “a limitless variety of faces.”

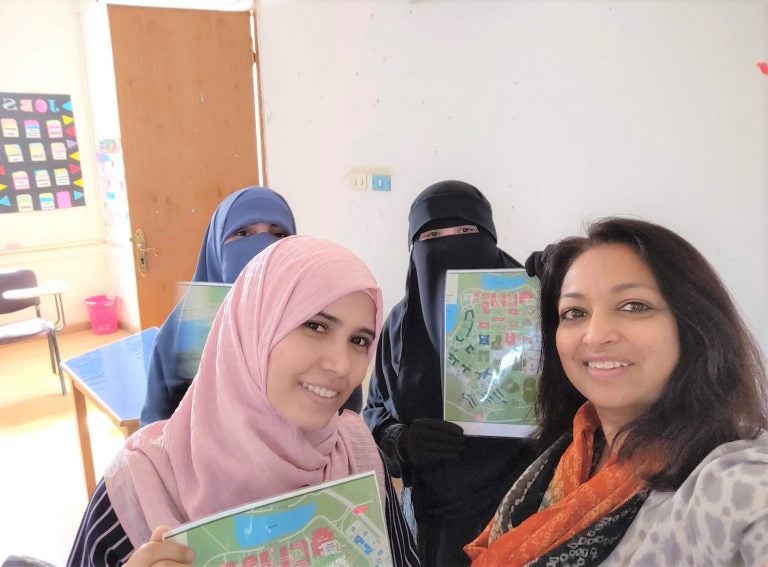

Natasha Agrawal, English Language Fellow, Egypt, 2019-2020

For Natasha Agrawal, a Fellow in Egypt (2019-2020), explaining her Americanness to her students and colleagues at Al Azhar University and the American Center in Cairo was somewhat more complicated. Agrawal, born and raised in Delhi, immigrated to the United States after graduate school, settled in New Jersey, and became a citizen. A few years ago, she decided to take a sabbatical from her long career as an ESL teacher in public schools to accept the fellowship posting to Egypt. “Being chosen to represent the United States overseas was a huge honor,” she says. But it was not until she visited the U.S. Embassy in Cairo that Agrawal realized the magnitude of her journey from Delhi native to Fellow in Egypt. Years earlier, Agrawal had stood outside the U.S. Embassy in Delhi, waiting in a long line to obtain a visa to the United States. “For hours, all I saw were big, tall walls, no building. I wondered, ‘Will I ever reach the end?’” she recalls. “If you’ve never experienced that, you don’t realize what a huge privilege it is to be welcomed into a U.S. Embassy as a Fellow, to have someone say, ‘Let me show you around.’ My mind was completely blown.”

However, Agrawal also had issues to address in Egypt, primarily stemming from her heritage. She recalls when she first entered the American Center, students looked at her and whispered to one another. When she spoke, shouts of “I told you she was Indian!” followed. Agrawal asked them if they were curious about her accent and explained that, yes, she was from India but was also American. “I’ve lived in the United States for 30 years, and I am so proud to be standing here in front of you, representing the country. Everyone stood up and clapped. I was so taken aback – it was a beautiful moment.”

Agrawal asked them if they were curious about her accent and explained that, yes, she was from India but was also American. “I’ve lived in the United States for 30 years, and I am so proud to be standing here in front of you, representing the country. Everyone stood up and clapped. I was so taken aback – it was a beautiful moment.”

Agrawal never denied her Indian background but rather used it to connect to her students and colleagues at the American Center and Al Azhar. She would talk about how Cairo, with its dust-filled congested streets, crowded buses, and stray animals, reminded her of Delhi. At the Center, where she led classes, conversation clubs, movie discussions, and more, she would share stories of her visits as a student to the American Center in Delhi, where she would chat with friends, study, and find relief from the city heat. “I’ve been in your shoes,” she told them. Teaching assistants at the university also bonded with Agrawal over their similarities as women of color, the language commonalities between Arabic and Hindi, and her knowledge of Indian culture— India’s soap operas and clothing are popular in Egypt. “They would tell me, ‘You’re American, but you’re one of us. Come, let’s talk,’” she recollects. “Then over tea, they would tell me personal stories about their lives. They connected with me as an Indian American.”

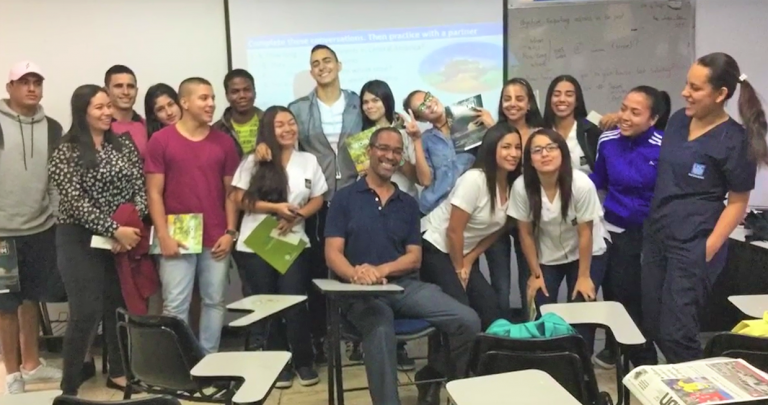

Peter Edwards, English Language Specialist, Colombia, 2016

Dr. Peter Edwards, a Specialist in Colombia (2016), also felt at home in his host city, Cali. He found it more ethnically and culturally diverse than the larger cities of Bogota and Medellin, and, as an African American, he fit in among the darker skin tones of the local population. Brought in to advise on strengthening the English language program at Universidad Santiago de Cali, Edwards knew he had the credentials and expertise to help the program. But when Edwards first met with administrators at the university, they responded in a very familiar way. “When I walk into a room and everyone is surprised, I know immediately what’s going through their minds – ‘Oh, this is an African American person,’” he says. “They are typically unbalanced and unfamiliar with the situation, whereas I am very balanced and familiar with it. I’ve been through this a million times, so I’m one step ahead.”

Edwards has coined a term for this phenomenon: lunacy, as in foolishness, but also as in luna, the Latin word for moon. He makes an analogy with the daytime moon. “Every once in a while you look up and see the moon midday. You don’t think about it much, but still, there it is, the moon in the middle of the day. It’s kind of strange and surprising,” he says. “That’s me when I teach abroad, popping up into people’s experience. I’m unexpected.”

Unexpected but familiar. Edwards notes that in Cali, as in every other place he has taught overseas, people could rattle off names of numerous African American men – Barack Obama, Martin Luther King, Jr., Michael Jordan, Jay-Z, and more – but they had never spoken nor been in the room with one. “I see these as opportunities to dispel misconceptions and find commonalities,” he says. In Colombia, for example, his colleagues would talk with him about the negative image of Colombia abroad, particularly as depicted in the then popular television series Narcos, which focused on Colombia’s powerful and violent drug cartels. Edwards would compare it to the negative stereotypes of Black Americans – also reinforced by media depictions – and the conversation would flow from there.

Ramin Yazdanpanah, English Language Fellow, Vietnam, 2017-2018

Making that connection as a BIPOC Fellow or Specialist is critical if a more inclusive understanding of the term American is to take root, says Dr. Ramin Yazdanpanah, a Fellow in Vietnam (2017-2018). Yazdanpanah – father, Iranian; mother, Cuban – considers much of his work as an educator is “to challenge those ideas of ‘the typical American’ and broaden the definition,” he says. “I am as American as someone named Smith.” In his classes and workshops in Vietnam, Yazdanpanah showed images of the Vietnamese markets in Louisiana, home to thousands of Vietnamese who immigrated to that state after the Vietnam War. “These are Americans, and they look just like you,” he told them.

We can and should talk about diversity, but we can also play music together, which connects us no matter our differences,” says Yazdanpanah. “It all builds rapport and trust.”

That inevitably led to a conversational detour about the war – many Vietnamese wanted to talk about its impact on the United States and Vietnam. Yazdanpanah never shied away from those discussions. Sharing deeper and potentially sensitive areas of culture and identity is an important part of the intercultural exchange, he notes, no matter how difficult. “We are also there as learners, and my role was often as a witness, to be in that space with them and listen.”

Serious cross-cultural exchanges such as these are important, notes Yazdanpanah, but so are lighter ones. Yazdanpanah, a seasoned musician as well as an educator, is a master of the didgeridoo and handpan, one of the world’s oldest and newest instruments, respectively. He brought those instruments with him to Vietnam and would play for his classes. Although the students were not familiar with the instruments, they could relate to their uniqueness, reminiscent of many traditional Vietnamese instruments. That prompted discussions about musical genres, both long-standing and contemporary. Even better, Yazdanpanah’s performances were examples of diversity in action: a Persian-Cuban-American Fellow playing the didgeridoo – an aboriginal wind instrument from Australia –– and the handpan – an Afro-Caribbean steel drum that originated in Switzerland. “We can and should talk about diversity, but we can also play music together, which connects us no matter our differences,” says Yazdanpanah. “It all builds rapport and trust.”

Access a community-created DEI resource list from English Language Fellow and Specialist Alumni.