At an American Corner in Marneuli, Georgia, English Language Specialist Vincent Lauter witnessed a small but extraordinary reminder of the power of effective workshopping: a 16-year-old English Access Microscholarship student, adept in AI generation, walking her teacher through her process for video creation. That teacher’s shift from apprehension to curiosity, and the shifting role dynamics that accompanied this collective experience, resonates with what Lauter witnessed time and time again working with over 270 educators at AI-focused workshops in Georgia and Armenia. As he notes, “what began as cautious discussions about potential risks evolved into dynamic collaborative sessions where teachers and students found themselves as co-learners exploring their new shared reality.”

The success of Lauter’s Specialist project, which saw him leading a comprehensive five-workshop series focused on best teaching practices in AI for teachers in Georgia and Armenia, was in part due to the great need for such work regionally. Regional English Language Officer John Silver in Ankara, and Education and Cultural Affairs Specialists Lika Gumberidze and Hasmik Mikayelyan at the U.S. Embassies in Tbilisi and Yerevan, respectively, recognized that “while AI tools were proliferating rapidly in both countries, educators lacked frameworks for ethical integration and practical pedagogical strategies,” Lauter says. Beyond this, the needs of many participants were as dynamic as they were varied, with linguistics professionals, K-12 teachers, representatives of government-backed institutions, private educators, digital novices, and seasoned AI vets all learning together.

In many respects, Lauter notes, “English language teachers are perfectly positioned to empower students with the language skills to create clear, detailed, step-by-step instructions to control AI, and the critical media literacy skills to evaluate AI output.” The journey for those participants, from hesitation to curiosity and confidence in AI-integrated learning, is what makes his project’s story so compelling.

Structural Solutions in Georgia:

Collective Exploration and the PARTS Model

Thanks to foresight from Embassy staff and local partners, Lauter was able to focus on tailored materials for workshops in both countries that “prioritized co-creating resources that reflected regional educational contexts, linguistic diversity, and infrastructure realities.” In Georgia, this began at the Marneuli American Corner, where the aforementioned student’s guidance led to her teacher’s exposure to AI video generation. When audiences here and at the American Corner in Khashuri – along with the academics he met at Akaki Tsereteli University and Central University of Europe – asked questions about the dangers of AI misuse, Lauter found that usage of scaffolding for AI prompt development was most beneficial.

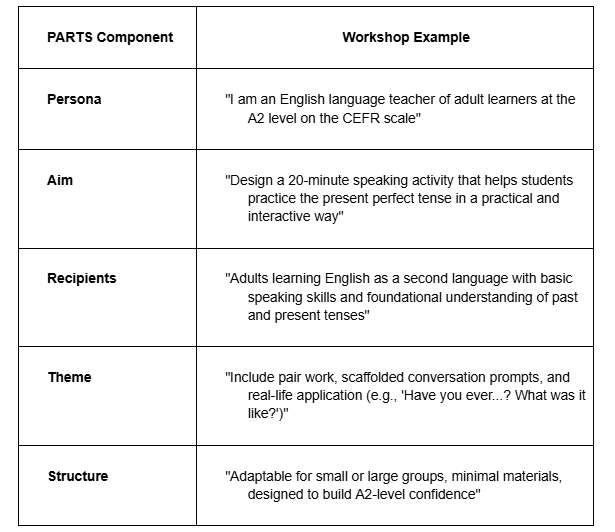

To this end, he employed the PARTS model (Persona, Aim, Recipients, Theme, Structure) to avoid technical jargon and instead provide simple instructions to a chatbot. The usage of such a model encapsulates one of Lauter’s key workshopping techniques – positioning AI as a partner in solving daily teaching challenges rather than as a threat. When using a model such as PARTS in a hands-on environment, he says, “the transformation from ‘AI will replace me’ to ‘AI can help me reach more students’” is immediate. The example below is aimed at an A2 English language learning audience. This participant brought a need for mixed-level speaking activities to the workshop, and within 20 minutes, had five practical activities for use in her classroom context.

The PARTS model is particularly useful for educators in that it looks in many respects like a lesson planning template – something teachers the world over are intimately familiar with. As the example above illustrates, Lauter pushed his audiences beyond theoretical frameworks into practical applications, a focus that “drove both engagement and sustained implementation” in his workshops.

Other highlights from those workshops – such as one Georgian university lecturer showing a rural primary school teacher how to adapt AI-generated materials for younger learners – reinforce Lauter’s belief that “the most transformative aspect wasn’t the content of the workshops, but the collaborative spaces they created.” When educators and students from major cities, small towns, and as many academic walks of life as can be imagined share challenges and solutions, he maintains, “innovation accelerates exponentially.”

Exploring AI Integration in Armenia

Building on the success of a week of workshops in Georgia, Lauter brought the same principles of peer learning and collaboration to over 170 educators from a wide array of academic backgrounds, interests, and skillsets in Armenia. This began with a session for over 50 primary and secondary teachers at the Children of Armenia Fund (COAF) SMART Center in rural Lori Province, which focused on best practices for integrating AI in a learning space while maintaining academic integrity. At the American University of Armenia (AUA) in Yerevan, 40 teachers from 12 different institutions explored AI assessment designs and the art of making assignments that work with (rather than against) AI capabilities.

Building on this momentum, the pace intensified during the remainder of the week. This included another workshop at AUA for 60 school teachers from around the country, sharing practical strategies for integrating AI tools into classroom activities while teaching students responsible AI use, and the opportunity to moderate a high-level roundtable discussion at the U.S. Embassy featuring more than 20 key stakeholders in the Armenian education system. To ensure broader community impact, the Specialist also led an AI in education workshop at the American Corner Yerevan for members of the public and met with leaders of the Armenian English Teachers Association (AELTA) to discuss future cooperation and professional development opportunities.

With so many audiences being addressed in such a tight timeframe, the question of sustainability became paramount, and led to perhaps the greatest innovation in Lauter’s project – the production of a comprehensive “AI for Education in Armenia” Canvas course that included all training materials, workshop activities, and classroom resources. As Lauter reflects, Canvas made strategic sense—many Armenian educators were already familiar with the platform through American English at State’s Online Professional English Network (OPEN) MOOCs.

Moreover, the team-focused features available on Canvas “allowed participants to become co-creators rather than passive consumers” of course content. The course evolved as educators added their own locally relevant examples, translated resources, and culturally specific applications. More significantly, it stands now as an evolving resource that participants continue to develop together. “Several participants have adapted the course structure for their own institutional training programs, creating a multiplier effect that extends far beyond our original reach,” Lauter says. By helping educators harness AI responsibly, Lauter’s project advances U.S. goals of promoting digital literacy, transparency, and open dialogue worldwide.

Building Trust Through Shared Uncertainty

Lauter acknowledges that any workshops focused on the power of learning how to leverage AI capabilities in learning environments will be met with pushback from various directions, often all at once. In the Caucasus and elsewhere, institutional administrators often worry AI can undermine teacher authority, for instance. Experienced educators can feel resentment at the thought of students teaching them about technology. Even some students, accustomed to clear rules and hierarchies, can feel uncomfortable with group decision-making rather than top-down guidelines. Perhaps most vocally, parents and community members often ask whether teachers are properly qualified to teach if they need to learn alongside their students.

Lauter’s response consistently reframes the student-teacher dynamic, positioning AI as a tool for enhanced rather than diminished teacher agency. Students might discover new tools or features, in this sense, but teachers determine the educational value, ethical implications, and curricular integration of those tools. Just as importantly, he stresses the need to acknowledge that all of us – teachers, learners and families alike – are navigating AI’s rapidly evolving capabilities together. “When teachers and students navigate uncertainty together, when they acknowledge mutual learning needs, and when they collectively solve problems,” he says, “trust deepens in ways that enhance all educational interactions, not just those involving technology.” The key to building that trust, in his view, is patient, systematic implementation of activities that honor and give agency to the existing expertise of learners while creating space for new possibilities.

The Paradigm Shift: Beyond Tool Mastery

Looking back at the challenges and breakthroughs of workshops in both countries, Lauter identifies one thing that surprised him the most throughout this project. In 2025, educators and learners have largely moved beyond the “shiny new toy” fascination with AI tools that predominated in 2023 and 2024. Tool mastery has become less of a focal point for users, in other words, in lieu of philosophical considerations for ethical and effective classroom use. “Participants didn’t want to simply use AI tools,” Lauter says of those he met at workshops. “They wanted to develop meta-strategies for making any AI tool more culturally responsive and educationally appropriate.

The innovations that emerged from that shift are reflected in the success of participants in Lauter’s workshops: peer review systems where students analyzed AI bias, cross-cultural projects examining different AI responses to similar prompts, and support structures for maintaining academic integrity while leveraging AI capabilities. As Lauter reflects, “The constant question became not ‘Does this AI tool work for our students?’ but rather ‘How do we help our students develop the critical thinking skills to work thoughtfully with AI?'”

Agency in the Age of AI: New Phases

The Access student in Marneuli wasn’t just demonstrating technical proficiency — she was participating in a fundamental reimagining of how knowledge flows in educational spaces. Likewise, her teacher’s shift from apprehension to curiosity represents the courage to model intellectual risk-taking and shared problem-solving — the idea that we all have something to learn in the age of AI. The sustainability of these workshops matters particularly because of English language teachers’ unique positioning today. Most AI tools are powered by Large Language Models, making language skills fundamental to using them effectively. As Lauter observes, “English language teachers give people agency in the age of AI through both the language skills to control AI systems and the critical media literacy skills to evaluate their output.” The work he helped catalyze in Armenia and Georgia continues not because the project demands it, but because educators now possess the models, confidence, and networks to lead their communities through ongoing technological change. With a second phase of this project now underway in both countries, the promise of that work has never been greater.

Vincent Lauter is a TESOL instructor and instructional designer at Arizona State University, where his pioneering work bridges critical media literacy and AI education in innovative ways. As a Specialist with the U.S. Department of State’s English Language Programs, he has led international teacher training initiatives, most notably the “AI for Education in the Caucasus” project that reached over 270 educators across Georgia and Armenia in 2025 and “English for Media Literacy Across Turkiye,” which reached more than 400 in 2024. His approach to AI literacy training emphasizes critical evaluation over tool mastery, helping educators and students develop sophisticated frameworks for assessing algorithmic bias, cultural responsiveness, and ethical technology integration.